Gene therapy for hemophilia A reduces bleeding in clinical trial

12 adults were tested as part of a investigator-initiated trial in China

GS1191, a gene therapy in the pipeline of Gritgen Therapeutics, increased factor VIII (FVIII) activity in the blood of people with hemophilia A taking part in a small clinical trial in China, resulting in fewer bleeding episodes.

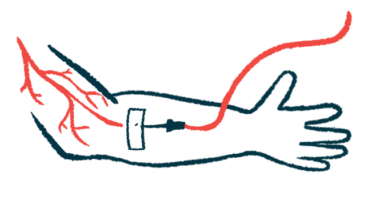

The fully enrolled investigator-initiated trial (ChiCTR2300073179) is testing the safety and preliminary efficacy of a one-time injection into the vein of GS1191, at a dose of 2E12 or 4E12 vector genomes per kilogram of body weight (vg/kg), in 12 adults with severe hemophilia A.

All the patients have been followed for at least 12 weeks (about three months) after dosing. Most side effects reported with GS1191 were mild and none were serious, suggesting the gene therapy may be safe.

“The outstanding safety and efficacy data from [the investigator-initiated trial] have instilled immense confidence in the entire team,” Wu Fenglan, co-founder and CEO of Gritgen, said in a company press release.

The company has launched a Phase 1 clinical trial to assess the safety, preliminary effectiveness, and pharmacokinetics of a single intravenous injection of GS1191 at different dose strengths. Pharmacokinetics refers to how a medicine moves through the body.

Gene therapy for hemophilia A

The trial was cleared to start by regulators in China early this year and the first patient was dosed in August, according to the company. Its findings are expected to inform the dose for future Phase 2/3 studies.

“Gritgen is committed to developing innovative gene therapy products, revolutionizing the quality of life of patients at the genetic level, and reshaping the clinical treatment pattern of hemophilia A,” Fenglan said.

Hemophilia A is caused by mutations in the F8 gene, which provides instructions for making FVIII, a clotting protein. When FVIII is faulty or missing, the blood cannot clot properly to stop bleeding. Without the protein, people with hemophilia A may have heavy, prolonged bleeding episodes that occur spontaneously or as a result of an injury or trauma, and can be difficult to control.

GS1191 is designed to deliver a working version of the human F8 gene via a single intravenous injection. The working gene is packaged aboard a delivery vehicle made from an adeno-associated virus (AAV), which is harmless to humans.

By addressing the root cause behind hemophilia A, the gene therapy should increase FVIII activity in the blood over the long term, thereby helping to prevent or reduce bleeding episodes.

The trial has an open-label design, meaning both the investigators and patients are aware of the treatment being given. Six patients received GS1191 at a dose of 2E12 vg/kg, and six at a higher dose of 4E12 vg/kg.

Early data showed GS1191 can consistently increase FVIII activity in the blood, resulting in patients having fewer bleeding episodes. Those given the higher dose reached normal FVIII activity levels and had no bleeding episodes after dosing.

Most side effects were mild and no serious side effects were reported in any patients, indicating GS1191 may have a favorable safety profile.

“We appreciate the investigators, patients, and their families, as well as our own team, for bringing effective and valuable treatment to [hemophilia A] patients,” Fenglan said.