Acute Brain Hematoma in Hemophiliac Treated Without Sudden Surgery in Case Study

Written by |

Treating a spontaneous brain hemorrhage in patients with hemophilia may be less risky if the acute hematoma is converted into a chronic hematoma, which is easier to treat, according to a case report published in the International Journal of Surgery Case Reports.

In the report, “Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage In Hemophiliacs — A Treatment Dilemma,” the authors discuss the difficulties faced by doctors treating a hemophilic patient with a spontaneous right subdural hematoma (the accumulation of blood under the skull, putting pressure on the brain). The doctors have to weigh the risks of operating and bleeding that may be difficult to control in a hemophiliac, or a conservative approach that risks swift deterioration and can carry high costs. No guiding treatment protocols exist.

In this case study, physicians choose a more conservative approach, converting the acute hematoma into a chronic one followed by, using treatments to control hemophilia, a burr hole evacuation.

The patient, a 32-year-old doctor, came to the hospital with complaints of progressive drowsiness and altered perception, as well as headache and vomiting. He had no history of trauma. The patient also had bradycardia (slow heart rate). Neurological exams revealed he was disoriented and drowsy, and could only obey simple commands.

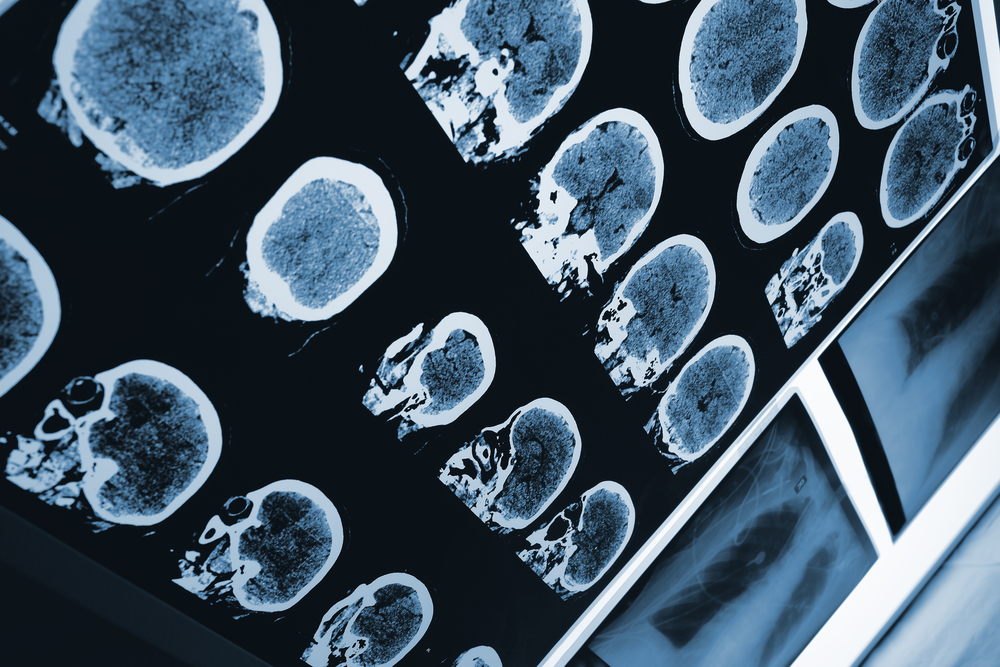

A computed tomographic (CT) scan of the brain found an acute hematoma in the right fronto-temporo-parietal lobe.

After discussion with the patient’s family, doctors chose to try a conservative approach, based on correcting his hemophilic profile through a three-day infusion of an anti-hemophilic factor (AHF). However, by five days post-admission, the doctor appeared to be significantly drowsy and his bradycardia had worsened.

The conservative approach, a combination of decongestants and AHF, was continued. But by day seven, the patient had developed pupillary asymmetry (abnormalities in the pupils), with further loss of perception. With the family’s approval, doctors decided to perform an emergency burr hole (a hole in the cranium) to evacuate the hematoma, while maintaining AHF, and under general anesthesia. The patient received pre-operative and post-operative transfusions of AHF to maintain its levels.

Six hours after the surgery, he was alert, active and oriented, and a new CT scan showed complete evacuation of hematoma. Infusions of factor 8 were continued at maintenance doses for the next seven days, after which the patient was discharged. No complications were reported during follow-up.

“Small volume bleeds with insignificant mass effect … may be managed conservatively with AHF and close neurological monitoring, allowing spontaneous resolution of hematoma,” the authors wrote. “Larger bleeds, like the current case, should be operated under the cover of AHF. In our case we were able to successfully convert the acute subdural hematoma to a chronic subdural hematoma under cover of decongestants and AHF.

“Only once the patient was neurologically [lethargic], surgical evacuation was contemplated. This avoided the need for craniotomy and the relatively high risk of rebleed.”

They added: “This technique not only significantly reduced the morbidity of craniotomy and rebleed but also gave a good functional outcome (Glasgow Outcome score of 5). The drawbacks of the above management technique included the high costs of AHF and the ambiguity of constant deterioration of the patient.”