FVIII Gene Therapy Directly into Joints May Best Protect Against Damage

Written by |

Gene therapy delivering the blood clotting factor VIII (FVIII) — whose lack causes hemophilia A — into the joints did better at protecting against hemophilic arthropathy (joint damage) than did administration into the bloodstream, a study in mice suggests.

Its findings support the potential use of FVIII injected directly into the joints instead of systemically (into blood circulation) for easing joint damage in people with hemophilia A.

The study “Exploring the potential feasibility of intra-articular adeno-associated virus-mediated gene therapy for hemophilia arthropathy” was published in the journal Human Gene Therapy.

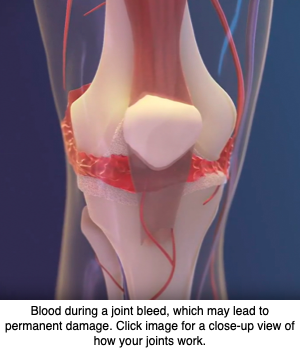

Hemophilic arthropathy often develops in people with severe hemophilia. The disease is characterized by permanent joint damage, a long-term consequence of repeated hemarthrosis (bleeding into joint spaces).

Despite significant improvements in its management, hemophilic arthropathy remains a major concern. It shares similarities with rheumatoid arthritis, an autoimmune disorder that also affects the joints. Notably, gene therapy delivered directly into the joints is also showing promise as a potential therapy for rheumatic diseases.

A research team from China and the U.S. previous used a mouse model engineered to lack the clotting factor IX (FIX) — the missing or defective factor in people with hemophilia B — to show that direct injection of FIX into the joint space protected against inflammation of the synovial membrane (synovitis) that lines the joints.

These researchers also showed that a gene therapy delivering FIX using a modified and harmless adeno-associated virus (AAV) might protect from bleeding-induced joint damage.

Now, the scientists investigated whether injecting the recombinant (engineered) human FVIII directly into the joints could protect from bleeding-induced joint damage. Since patients treated with replacement therapy using FVIII are more prone to develop antibodies against this clotting factor, called inhibitors, the researchers also assessed the risk of inhibitor formation after repeat injections of FVIII.

Similar to what they had seen in mice lacking FIX, animals without FVIII given three doses of the missing clotting factor directly into their joints were better protected against synovitis, compared to mice given FVIII into blood circulation.

In addition, improvements seen with joint-injected FVIII at a dose of 25 IU/Kg were superior to those seen with a four times higher dose of FVIII injected into a vein (100 IU/Kg). Levels of FVIII within the joint space increased up to two days after injection into the joints, while no changes were seen in the activity of FVIII in blood circulation.

Researchers then evaluated how the presence of FVIII inhibitors affected the efficacy of joint-injected FVIII. After inducing inhibitor formation, the scientists injected FVIII into the blood (100 IU/Kg) or joints (25 IU/Kg) of mice.

Two weeks after also inducing hemarthrosis, the animals developed inflammation in the joints, as shown by a synovitis score of 6.8. FVIII given into the blood did not ease synovitis, as shown by a score of 6.3. In contrast, injections into the joints significant lessened the inflammation, with their synovitis score lowering to 1.7.

All mice given FVIII into the joint survived the needle injury to induce hemarthrosis, in contrast to 46% of those given FVIII into blood circulation.

Injecting FVIII into the joint did not increase the risk for developing FVIII inhibitors, experiments showed. When two groups of mice were injected with FVIII either into the blood or the joints at a dose of 100 IU/Kg/week for three weeks, all animals given FVIII to the blood developed inhibitors. In comparison, 50% of those injected into the joints developed inhibitors, and at a very low level.

These results showed that injecting FVIII directly to the joints “provided protection against bleeding-induced joint damage, even in the presence of inhibitor antibodies,” the researchers wrote.

Joint delivery of FVIII “associated with a lower risk of inhibitor formation, even in joints with pre-existing damage,” they added.

In addition to the detrimental effects of FVIII inhibitors, patients may carry antibodies directed against AAVs. As such, the team measured their levels in the blood and in the synovial fluid — a fluid that bathes the joints to protect them when moving — collected from 12 patients with hemophilic arthropathy.

Results showed that the levels of antibodies were in general low, especially in the synovial fluid.

This also supports the “feasibility of local expression of FVIII by gene therapy for the management of HA [hemophilic arthropathy],” the investigators wrote.