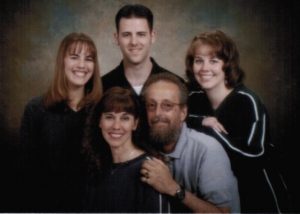

Grieving My Father’s Absence in My Hemophilia Journey

A conversation

Last night I dreamed that I spoke with my father. I asked him how he knew he had a bleed. Did his knee bubble like a soda? Was it tight, but not painful? I yearned for his input, but my alarm sounded before he was able to share. I pined for words I would not hear.

Grief is real. I miss my dad terribly.

My dad gave me hemophilia. He never knew the extent of the disease he passed to me. A few years before his death, I was labeled a “symptomatic carrier” — someone who not only carries the hemophilia gene but also experiences problematic bleeding. After I was diagnosed as a symptomatic carrier, I fell on my back; the injury took forever to heal. “Maybe you have a microbleed like I get,” my dad said. “Factor may help you heal faster.”

That was our only conversation about hemophilia.

My dad’s story

My dad was born a “bleeder.” His mother passed the mutation to him; my grandmother got the mutation from her father, and my great grandfather, who was also a “bleeder,” died of a brain hemorrhage without a hemophilia diagnosis. My father had a rough childhood of pain and social isolation. It took years and the death of his brother before he received a diagnosis — both boys had tonsillectomies, and while my father survived the surgery, his brother didn’t. Survivor guilt followed Dad for the rest of his life.

Dad was diagnosed with hemophilia after a bad knee bleed and a trip by train to New York to see a specialist. His life became one of physical limitations, fear of injury, and treatment with cryoprecipitate, or fresh frozen plasma. He was eventually introduced to factor products, a great new treatment with new freedoms — but this freedom came to a crashing halt when he was infected with HIV and hepatitis by contaminated factor products. My father later contracted cancer. Battling the three took his life almost 10 years ago, just as I was beginning to learn what it meant to be a female with low factor levels. The timing sucked.

Grieving missed connections and support

When I attended my first retreat for women with bleeding disorders and learned that my factor levels were among the lowest in the room, I missed my dad. The ensuing discussions about my lack of treatment, compared to my female peers, were a wake-up call. I couldn’t discuss this with him.

When I attended advocacy training sponsored by the Hemophilia Federation of America with my sister, I missed my father. He would have been proud to see us in D.C., learning how to be a voice for individuals with hemophilia. He often discussed the ramifications that political decisions had on people with hemophilia. I wish he had been there, fighting for our family and the greater hemophilia community.

When I was hemorrhaging after a hysterectomy, I missed my daddy. I wanted him by my side. He would know what to do — he lived with the condition his entire life. I wanted his wisdom, his guidance, and his reassurance. I was scared and angry. I needed him, but he was not there. I felt robbed: I had been diagnosed too late to share this experience with the one person in my life who had the most advice to give. I have no doubt the hemophilia connection would have been meaningful to him as well, strengthening our father-daughter bond.

When I made the controversial T-shirt that read, “My dad gave me hemophilia. He was a symptomatic carrier,” I missed my father. I know he would have laughed and embraced the political statement. He would have stood by my side, fighting for treatment equity for women with hemophilia.

When I attended the first National Conference for Women with Hemophilia and read a poem I wrote, I missed my dad. I wanted to go home and share my experiences with him. I needed to ask him if he related to everything I now understood was connected with my hemophilia. I so desired to tell him how powerful it was to be in a room with over 100 women with hemophilia. I ached to share with him how I found my voice.

When I struggled with self-infusion, I wanted to pick up the phone and call my daddy for help. I wanted him to teach me. I know he would have been my number one supporter, but it was not meant to be.

I continue to learn and educate others about hemophilia. I have found fantastic sources of support and, for this, I am abundantly grateful. I will persevere on this journey and always advocate for women to receive appropriate diagnosis and treatment.

Not being able to share this experience with my father is the thing I hate the most about having hemophilia. Daddy, I miss you.

***

Note: Hemophilia News Today is strictly a news and information website about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or another qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. The opinions expressed in this column are not those of Hemophilia News Today or its parent company, Bionews Services, and are intended to spark discussion about issues pertaining to hemophilia.

Leave a comment

Fill in the required fields to post. Your email address will not be published.