Why I’m thankful for my delayed hemophilia diagnosis

Today, delays are unacceptable. But in the '80s, they may have been lifesaving.

Written by |

Today, when girls and women struggle to obtain a hemophilia diagnosis and proper treatment, I am angry. We need to do better.

A timely diagnosis is crucial, as delayed testing or treatment can endanger women — especially if they are in an accident that causes bleeding or if they need surgery. Those with a family history of hemophilia should be tested as early as possible.

Once diagnosed, women with hemophilia should wear a medical alert bracelet or tag for safety purposes. This ensures they’ll get the care they need in the event of an emergency.

In today’s world, it is unconscionable to think a female patient would be denied testing or have a hemophilia diagnosis delayed, but unfortunately, it still happens.

A different perspective on the past

When I attend conferences for women with bleeding disorders, it’s not uncommon for me to encounter people who are incredibly resentful about their delayed diagnosis. If these women are older than 40, I offer them a different perspective — one of immense gratitude.

Let me share a story with you:

When I was 10 and my sister was 4, my parents took us to the hemophilia treatment center at the Luskin Orthopaedic Institute for Children in Los Angeles, to have our blood tested. My father had hemophilia A, and his doctor, Carol Kasper, was a pioneer in treating women with the condition. She was one of the first to understand that women can have hemophilia and advocated for female patients to have their factor levels tested. (Hemophilia A is characterized by low levels of factor VIII, or FVIII, which is crucial in the blood clotting process.)

The nurse drew my sister’s blood right away. However, she missed my vein twice, and another staff member tried — unsuccessfully — another two times. My dad was irate. He yelled, “I infuse myself! I can hit veins better than you. If you miss again, I will poke my daughter myself!”

Between the repeated needle pokes and my father’s frustration, my anxiety went through the roof. I screamed, then screamed some more, prompting the staff to call the pediatric “A team” to come draw my blood. More than an hour after the first attempt, this experienced team successfully drew my labs. I was pinned down by two adults, kicking and screeching, when they finally accessed my vein.

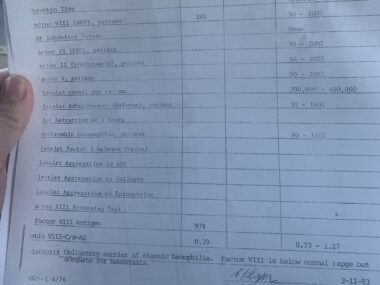

G Shellye Horowitz’s medical record from 1983 says, “Factor VIII is below normal range but adequate for hemostasis.” (Courtesy of G Shellye Horowitz)

At the time my sister and I were tested in 1983, it was believed that a FVIII level above 30% was adequate for hemostasis, the body’s process to stop bleeding, and that no treatment for bleeds would be necessary in one’s lifetime. In fact, when my father had treatment for bleeds, his FVIII levels were raised to 30%. (No wonder it took him so long to heal. Today, most centers in the U.S. maintain factor levels at 80%-90% for severe, life-threatening bleeds.)

Our test results came back within a few weeks. My sister’s FVIII level was 36%, which is pretty accurate for her to this day. I had a FVIII level of 38%. We were told that our levels were high enough that we’d never need FVIII replacement. Even though I had significant bleeding throughout my childhood and into adulthood, hemophilia was never considered as a cause, as my factor levels were “fine.”

It wasn’t understood back then that stress raises FVIII levels. The trauma of the blood draw likely increased my level to 38%. Now that I have a hemophilia diagnosis, I know my actual FVIII level ranges from 11% to 22%, which would have placed me on the radar for treatment even in 1983.

I am so grateful

My dad always believed in innovation and wanted the best and newest treatments. When a new FVIII replacement product emerged in the 1980s, he was among the first to adopt it. Unfortunately, this was at the beginning of the tainted blood scandal, in which 90% of people with severe hemophilia were infected with HIV, among other blood-borne diseases. My father contracted both HIV and hepatitis.

I wish I could thank the nurse who missed my vein. My father made her miserable that day. If she had hit my vein on the first try, the test results might’ve shown my true lower FVIII levels. My dad certainly would have advocated for me to also use the new product to treat the many bleeds I experienced as a child. It’s almost guaranteed that I would’ve been part of the 90% who contracted HIV. A majority of them died. Had I used that treatment, I most likely would not be here today.

Ironically, the lack of recognition and treatment I received in the ’80s saved my life.

Today, it is reprehensible when a woman is not diagnosed in a timely manner. And yet, I will always be thankful that I was gifted with a delayed hemophilia diagnosis — and saved from HIV exposure — by a traumatic blood draw.

Note: Hemophilia News Today is strictly a news and information website about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or another qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. The opinions expressed in this column are not those of Hemophilia News Today or its parent company, Bionews, and are intended to spark discussion about issues pertaining to hemophilia.

Leave a comment

Fill in the required fields to post. Your email address will not be published.