Hemophilia diagnosis and testing

In hemophilia, the blood isn’t able to properly form clots, resulting in easy, prolonged, and heavy bleeding. Blood tests to detect clotting abnormalities are the definitive way to establish a diagnosis of hemophilia.

Hemophilia is caused by a deficiency of specific proteins that help blood clot, called clotting factors. Each type of hemophilia is marked by the loss or malfunction of a different clotting factor — factor VIII in hemophilia A, factor IX in hemophilia B, and factor XI in hemophilia C.

Most often, genetic mutations lead to low levels of clotting factors, so a family history of hemophilia frequently motivates an evaluation for the bleeding disorder. However, not everyone with a genetic form of the disease has a family history. In rare cases, hemophilia arises due to an immune system malfunction rather than genetics. This is called acquired hemophilia. In these instances, early signs of hemophilia, such as excessive bleeding and bruising, may prompt diagnostic testing.

Family history

About two-thirds of babies diagnosed with hemophilia have parents or other relatives with the disease. As such, recognizing a family history is often a crucial first step in diagnosing hemophilia.

The inheritance pattern of hemophilia varies depending on the disease type. The mutations that cause hemophilia A and B are found on the X chromosome. These types of hemophilia mainly affect males, who have only one X chromosome. Females who have two X chromosomes — one with a hemophilia-causing mutation and one without — don’t usually develop serious hemophilia symptoms. However, they can still pass the disease-causing mutation to their children, and are known as carriers. Hemophilia C is inherited through different patterns and affects both males and females equally.

For people with a family history of hemophilia who wish to have children, genetic testing and counseling can help them understand the risk of passing along a disease-causing mutation. For women who don’t have symptoms but have a relevant family history, this process is known as hemophilia carrier testing.

When there is a family history of hemophilia, genetic testing for hemophilia during pregnancy can help determine if the developing fetus will have hemophilia or be a carrier. For these tests, physicians examine a sample of fetal cells to determine if they harbor mutations that cause hemophilia.

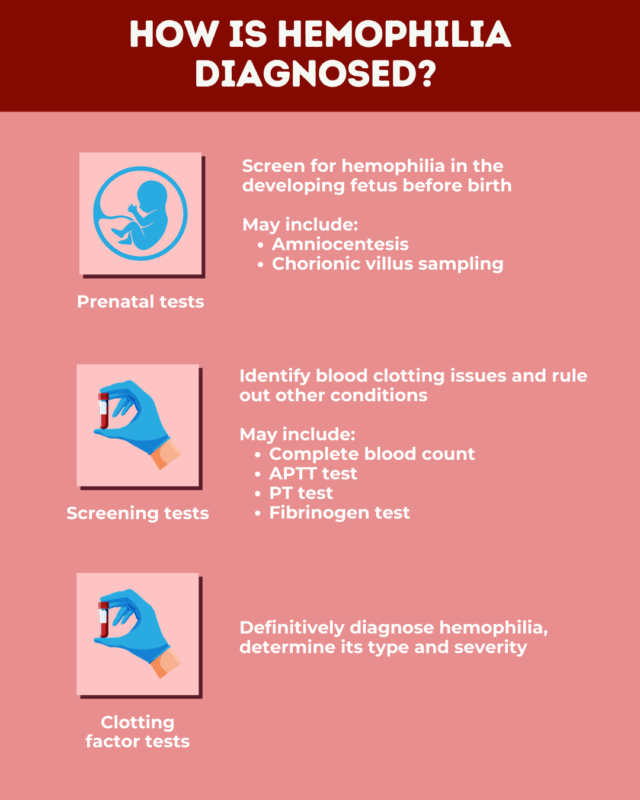

The two methods most commonly used for hemophilia testing during pregnancy are:

- amniocentesis, which involves using a needle to remove a small amount of the amniotic fluid that surrounds the fetus in the womb, usually during the second trimester of pregnancy

- chorionic villus sampling, which involves threading a thin tube through the vagina and cervix after the 11th week of pregnancy to remove a small tissue sample from the placenta, the temporary organ that provides oxygen and nutrients to the developing fetus

If prenatal testing is not done, an at-risk infant can be tested for low clotting factor levels at birth using a small blood sample from the umbilical cord.

This approach is more accurate for hemophilia A than hemophilia B. That’s because factor IX, the clotting protein missing in hemophilia B, is at lower-than-normal levels even in healthy newborns, so a mild deficiency doesn’t necessarily indicate the bleeding disorder is present. Repeat testing may be necessary in such cases later on.

Blood tests

While family history and genetic testing are useful in identifying individuals at risk, blood tests to confirm low levels of clotting factors are the only definitive way to diagnose hemophilia.

Blood tests for hemophilia can be divided into two broad categories:

- screening tests: general assessments of blood health and clotting ability

- clotting factor tests: measurements of the activity of specific clotting factors

Screening tests can help rule out other conditions that affect blood clotting, while clotting factor testing can help definitively diagnose hemophilia and pinpoint its type and severity. Additional tests may also be performed to distinguish between genetic and acquired forms of hemophilia.

Screening tests

Screening for general blood health and clotting ability is a vital step in testing for inherited bleeding disorders, such as hemophilia. While such tests cannot definitively diagnose hemophilia, they can confirm that a person has a blood-clotting disorder and also help rule out other conditions that cause bleeding.

Such tests may include:

- Complete blood count (CBC): provides information about the health of blood cells

- Activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) test: measures how long it takes for blood to clot, indirectly assessing clotting factors linked to hemophilia

- Prothrombin time (PT) test: measures how long it takes for blood to clot, indirectly assessing the activity of clotting factors not linked to hemophilia

- Fibrinogen test: measures the activity of fibrinogen (factor I), which is involved in the final step of blood clotting but is not affected in hemophilia

Complete blood count

A CBC is a standard test that measures:

- the size and number of oxygen-carrying red blood cells

- the amount of hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying protein inside red blood cells

- the number of infection-fighting white blood cells

- the number of platelets, the cell fragments that play a key role in blood clotting

People with hemophilia usually have normal results on a CBC test. However, a recent bleeding episode can result in anemia, or low levels of red blood cells and/or hemoglobin.

Like hemophilia, low platelet counts can cause abnormal bleeding, so a CBC can help rule out low platelet counts as a possible cause of symptoms.

Activated partial thromboplastin time test

An APTT test measures how long it takes for a clot to form in a blood sample. It indirectly assesses the function of key clotting proteins, namely factors VIII, IX, XI, and XII, which include all the proteins whose deficiency can cause hemophilia A, B, and C.

This means that people with any of these hemophilia types typically have abnormal APTT results, with blood taking longer than normal to clot. However, it doesn’t identify which specific clotting factor from the group is deficient and, therefore, cannot distinguish between hemophilia types.

The test is also not specific to hemophilia, and an abnormal result can be the consequence of other health conditions. Moreover, people with milder forms of hemophilia can have normal APTT results, so a normal test result doesn’t necessarily mean hemophilia is not present.

Prothrombin time test

Similar to the APTT test, the PT test measures how long it takes for the blood to clot. But it does so by evaluating the activity of a different set of clotting factors, specifically factors I, II, V, VII, and X.

People with the most common types of hemophilia have normal levels of all these clotting factors, so normal PT test results are typically expected. This test can also help rule out other clotting disorders.

Fibrinogen test

Fibrinogen, or factor I, is a protein involved in the final steps of blood clotting. This test measures the amount of fibrinogen in the blood and assesses its effectiveness. Fibrinogen is not missing in any type of hemophilia, so people with hemophilia usually have normal results on this test.

Clotting factor tests

Clotting factor tests, also known as factor assays, measure the activity of clotting factor proteins in the blood. This is the most definitive method for diagnosing each type of hemophilia. For example, an abnormal factor VIII test can confirm hemophilia A, while an abnormal factor IX test can confirm hemophilia B.

Results from clotting factor tests are usually given as a percentage of normal activity. Theoretically, a person without hemophilia would have about 100% normal factor activity. However, activity levels can vary naturally, and activity between 50% and 150% is generally considered normal.

Hemophilia is typically diagnosed when clotting factor activity is less than 40% of normal. Different activity levels are associated with different hemophilia severity levels:

- in mild hemophilia, clotting factor activity is higher than 5% but less than 40%

- in moderate hemophilia, clotting factor activity ranges from 1% to 5%

- in severe hemophilia, clotting factor activity is lower than 1%

Determining the specific type and severity of hemophilia is important for creating an individualized treatment plan.

According to current treatment guidelines, people with moderate or severe hemophilia should receive regular prophylactic treatment to prevent serious bleeds. After a mild hemophilia diagnosis, patients may only receive treatment to manage bleeds as they arise.

Tests to identify acquired hemophilia

The results of standard blood tests used to identify hemophilia will look similar for both genetic and acquired forms of the disease, namely an abnormal APTT and low clotting factor activity.

Acquired hemophilia, which typically develops in adulthood, occurs when the immune system produces antibodies that target a specific clotting factor, usually factor FVIII, preventing it from working correctly. To identify this type of hemophilia, doctors may run additional blood tests to detect the presence of these antibodies, known as Bethesda assays.

They may also perform a mixing study, in which a sample of the patient’s blood is mixed with healthy blood before the APTT test is performed. In genetic forms of hemophilia, adding healthy blood containing the missing clotting factors will improve the test results. But in acquired hemophilia, where antibodies are attacking clotting factors, mixing in healthy blood won’t help.

Signs to get tested

While infants with a family history of hemophilia may get tested shortly after birth, about one-third of babies born with hemophilia don’t have a known family history. In these cases, the emergence of certain symptoms usually indicates when to test for hemophilia. These may include:

- spontaneous bleeding: bleeding without a clear cause

- prolonged or heavy bleeding: excessive bleeding after an injury or a medical procedure that punctures the skin, such as circumcision, vaccination, or surgery

- excessive bruising: substantial bruising, reflecting bleeding under the skin, after even mild injuries

- hematomas: a type of raised bruise that appears as painful lumps on the skin from more significant under-the-skin bleeds

With severe hemophilia, bleeding-related problems often become evident in the first few months of life, prompting a diagnosis while patients are still infants. A possible sign of hemophilia in infants is bleeding in the head during birth, particularly if assistive devices like forceps or a vacuum were used during delivery.

In cases of moderate or mild hemophilia, signs of excessive bleeding might not become apparent until later in childhood, adolescence, or even adulthood. After infancy, a common sign of hemophilia is excessive bruising as the child starts to crawl and walk.

When diagnosing hemophilia in adults, symptoms could also include heavy menstrual bleeding or excessive bleeding after childbirth.

A healthcare provider can help patients and families identify when blood tests for abnormal bleeding are appropriate and learn where to get tested for hemophilia. A blood disorder specialist, called a hematologist, is typically involved in diagnosing hemophilia.

What happens after a hemophilia diagnosis

After a clotting factor test identifies the presence of hemophilia, patients may be offered genetic testing to confirm the presence of a disease-causing mutation.

Newly diagnosed hemophilia patients should work closely with their healthcare team to develop a personalized treatment and monitoring plan. Where possible, it is advisable to seek care from a hemophilia treatment center, where patients can work with a specialist hematologist who has expertise in the bleeding disorder.

Hemophilia News Today is strictly a news and information website about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.

Fact-checked by

Fact-checked by